acoustic center

sound radiation

What is the acoustic center?

In many practical acoustics applications, it is convenient to represent a complex-shaped, distributed source as if it behaved as single point source. This makes it simpler to calculate 1/r decay curves, which are used in free-field microphone calibrations or in evaluating anechoic chambers. The location of this equivalent point source is considered to be the acoustic center of the source.

How is the acoustic center typically defined?

The definition of the acoustic center appears in several standards. ANSI terminology defines the acoustic center as “the position of the virtual point source from which sound pressure varies inversely as distance” whereas IEC61094-3-2016 defines it as “the point from which … spherical wave-fronts … appear to diverge.” However, over the years, researchers have not always agreed on how precisely to think and define the acoustic center.

Some of the earliest conceptions of the acoustic center related to directivity measurements: when measuring the sound radiation of a loudspeaker by placing it on a turntable, an important question is what point of rotation whould be used. Measurements made when the pivot point aligns with the source’s acoustic center woud produce perfectly omnidirectional directivity patterns. However, if the pivot point and acoustic center don’t align, slight distortions appear in the measured pattern, leading to an ‘egg-shaped’ beam pattern.

However, in 1977 Trott suggested that a better definition would be the “locus of the equivalent point source that yields the same far-field pressure in magnitude and phase in a specified direction” instead of “an arbitrary center of rotation for determining the farfield directional response in terms of sound pressure magnitude.” This is the definitional concept that has seemed to stick throughout the following decades.

Building on this idea, researchers developed acoustic center localization techniques based on 1/r decays, phase delays, group delay, and matching wavefronts. However, in a significant paper published in 2006, Jacobsen et al. showed that these methods only agree at low frequencies when the wavelength is large relative to the radiating body. At high frequencies, different definitions give different acoustic centers for the same sources!

Over what frequency regimes is the acoustic center valid?

Trott’s definition of the acoustic center can be indiscrimantely applied at arbitrary frequencies. This has generally lead to the assumption that the concept of an acoustic center must be valid at arbitrary frequency. However, around the time of Jacobsen et al.’s work, Vanderkooy, interested in loudspeaker directivity measurements, devised a new low-frequency formulation. His idea was to take a multipole expansion of the Kirchoff-Helmholtz Integral Equation to represent complex sources as the superposiiton of a monopole and dipole field. He found that by moving the location about which the expansion is perfomred, one can eliminate the dipole component. This special position he termed the ‘low-frequency acoustic center’ and developed a two-point estimation approach for estimating its value for axisymmetric sources.

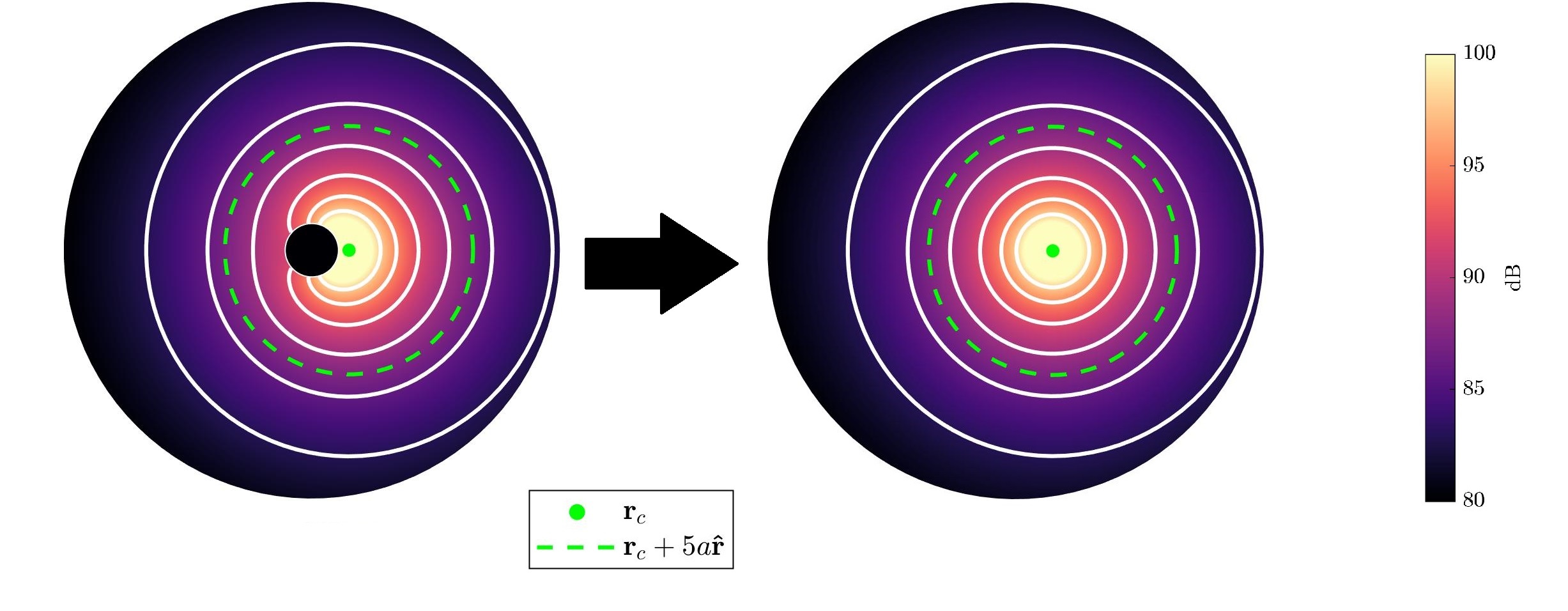

Later, Aarts and Janssen showed that the Legendre polynomial expansion coefficients give a closed-form solution to the acoustic center for axisymmetric radiators. A recent of work of mine showed how this can be generalized to the spherical harmonic expansion coefficients of arbitrary sources by considering the low-frequency acoustic center as the ratio of the dipole to monopole moment. Below is a result showing how the radiation from a point source on a sphere may be replaced by by an equivalent point source located at 1.5 times the radius of the sphere.

You can read more about the theory here: On the low-frequency acoustic center